Miles Davis Sextet: Kind of Blue

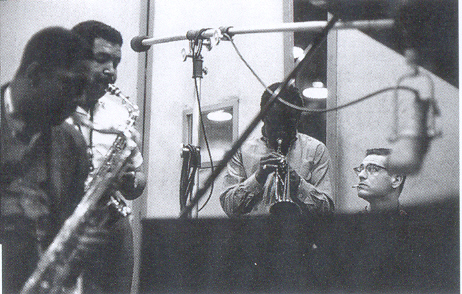

Miles Davis Sextet

Kind of Blue

Recorded in New York City – March 2, 1959 and April 22, 1959.

Jazz played by small groups rarely has anything written down. The sound is a spontaneous production of those musicians, in that group, at that time and place – and afterwards will not be repeated. The artist has to create the details and build the whole without chance of going back, like some forms of painting.

The context

This jazz recording from 1959 was made after Charlie Parker but before Civil Rights. In the late 40s and early 50s, Charlie Parker’s sweeping, rapid improvisational runs, often deliberately dissonant, had opened new pathways for jazz, and there was scarcely a jazz musician who didn’t show his influence. But Miles Davis (see GL Dec 2006) who played trumpet with Parker before forming his own groups, started a new style called cool jazz -few notes, picking the dissonances carefully, creating an atmosphere at once lyrical and remote. During 1958, he called into his group a young white pianist called Bill Evans (see GL March 2005), who had made his own innovations by the chords he played, finding new harmonies for old ballads, resolving from one key to another in new ways, with a bittersweet contained emotion. By early 1959, Bill Evans had left Miles’ group, and was making a successful career with his own trio. He was called back for these sessions.

Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream” speech was on August 23, 1963. Then he said: “the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land”. This was so true that once Miles Davis, taking a breath of air outside the club in New York where he worked, was beaten up by a white cop for no other reason than that he was standing there. In music, the outcry at this discrimination is the Blues, which somehow is the home base of jazz played by black musicians The traditional sequence of harmonies -in the key of F it is F/Bb7/F/F7/ Bb7/Bb7/F/F/ C7/C7/F/F – is the basis of the 12-bar blues, but on top of this the player improvises with great freedom, often using the “blue note” – the minor third of the chord, which emphasizes the cry of lament.

The other two soloists in Kind of Blue – John Coltrane playing tenor sax, and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley playing alto sax, are heirs both to the blues, and to the playing of Charlie Parker. Both in their early 30s, they would play jazz for hours every night, as all the musicians in the sextet, often the same tunes again and again. The other two musicians – Paul Chambers on bass, and Jimmy Cobb on drums, are both considered outstanding players from that time. The role of the bass was to remember the original harmonies and provide a driving, rhythmic underpinning; the drums complement the bass, playing a rhythm slightly behind the bass to make the music swing, and putting in different effects and interjections to support the soloist.

Jazz is usually built round a repeated sequence of harmonies, often that of the blues, or that of popular songs. However, by the mid-1950s the innovations in jazz in harmonies and improvisations had become so complex and dissonant that it was often difficult to follow what was going on at all, particularly for the layman.

Simplicity, freedom and spontaneity

So into this context Miles Davis conceived the music for Kind of Blue. He told the musicians what they would play at the session itself, and worked the arrangements out with them on the spot. The arrangement would encompass just the way to play the tune the first time through – after that the soloists were on their own, and the piano, bass and drums would invent their backing, keeping in mind the original tune, and picking up and complementing what the soloist was doing. After a few repeats (or choruses) from each soloist, the original setting would be repeated to end. The first time through would be the recording “take” – no other chances. And that’s what was recorded.

Track by Track

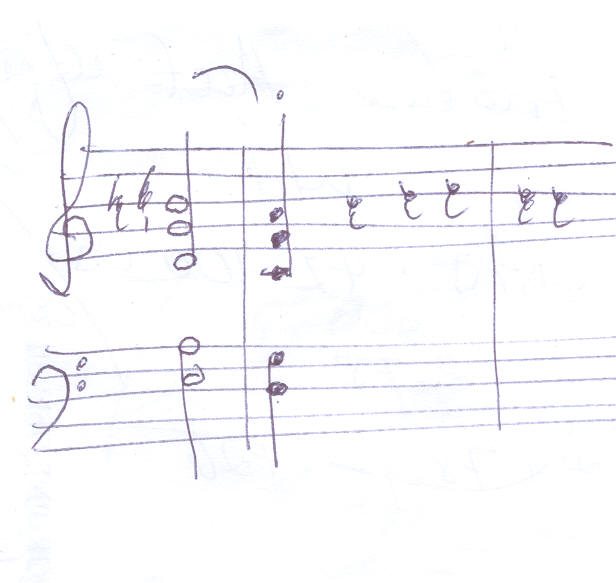

So What is the first track, which opens with some enigmatic chords from the piano. Then, unusually, the bass plays the theme, which is a little phrase which rises and falls,  followed by these chords from the piano, as if saying Sooooo what? If you play these on the piano, they sound unfinished, slightly bitter, and leave you hanging in the air. After four bass “questions” and answers from the piano, there is another four with answers from all the other instruments; the music then shifts half a tone upwards for four Q&As, and returns to the original tone for four more. After that, solos. What do you expect? Incoherent? Bitty? Sounding-out-of-tune? None of these things. Each player constructs strings of melody, each in his own style, sitting over the occasional changes of key as to the manner born – lyrical, restrained original. Not one of the clichés which may creep into any oft-repeated tune, even in jazz….. Miles knew what he was doing when he set it up that way!

followed by these chords from the piano, as if saying Sooooo what? If you play these on the piano, they sound unfinished, slightly bitter, and leave you hanging in the air. After four bass “questions” and answers from the piano, there is another four with answers from all the other instruments; the music then shifts half a tone upwards for four Q&As, and returns to the original tone for four more. After that, solos. What do you expect? Incoherent? Bitty? Sounding-out-of-tune? None of these things. Each player constructs strings of melody, each in his own style, sitting over the occasional changes of key as to the manner born – lyrical, restrained original. Not one of the clichés which may creep into any oft-repeated tune, even in jazz….. Miles knew what he was doing when he set it up that way!

Freddie Freeloader is the only track which has Wynton Kelly on piano, instead of Bill Evans. Wynton was the regular member of Miles Davis’s group at that time, and this is a 12-bar blues in Bb. Everybody sounds absolutely at home, and apparently this was the first track recorded. Wynton’s solo is authentic blues, while Miles sounds as bleak as ever. John Coltrane’s solo on tenor is a heartfelt cry for all the things Martin Luther King was talking about….. while Cannonball echoes the sentiment with less pain, but no less sincerity.

Blue in Green is a joint composition from Miles and Bill Evans, which is like viewing distant peaks while sitting on top of a mountain on a cold winter’s day. Cold, remote, and beautiful.

All Blues is the familiar 12-bar sequence, but this time, unusually, in 6/8 time. The theme, which is also serves as backing, is simple – 3 notes rising, then one coming back down. But this is where the skill comes in – the musicians develop this, each supporting the other…. first Miles, then Cannonball, leading to the monument of John Coltrane’s solo – wail, man, wail! Bill Evans opts for complex chords, before the 4-bar intro passage leads back to the theme, which is repeated to close.

Flamenco Sketches is another Bill-Evans-inspired piece. According to his description on the sleeve notes, it is “a series of five scales, each to be played as long as the soloist wishes until he has completed the series”. This freedom, and a slow pace, produces a series of gentle, melodic inventions from the soloists, without the suffering of the blues tracks. It is though, perfectly in the mood of the others, and of the album itself – restrained, coherent, sometimes enigmatic, and kind of blue throughout.

The Hype

If you look at amazon.com, or Internet references, you may get suffocated by the praise heaped on this record. Supposedly the biggest-selling jazz record of all time, it still sells well. It appeals not only to jazz musicians and fans, but to rock musicians, and even those without any previous contact with jazz. Some say they listened to it every day for years for its atmosphere, while many listen to learn from it about improvisation…. so…..

Good Listening!