Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125 (Choral)

Schwarzkopf/Höngen/Hopf/Edelmann

Choir and Orchestra of the Beyreuth Festival

Conductor: Wilhelm Furtwängler

Recorded 1951. EMI Classics References.

Beethoven’s 9th is considered one of the great musical works of all time. And of this particular recording a critic has said “I simply had no idea of what power, breadth, majesty, grandeur and originality this music contained until I heard Furtwängler”. So we are evidently talking (with due humility) about something very special.

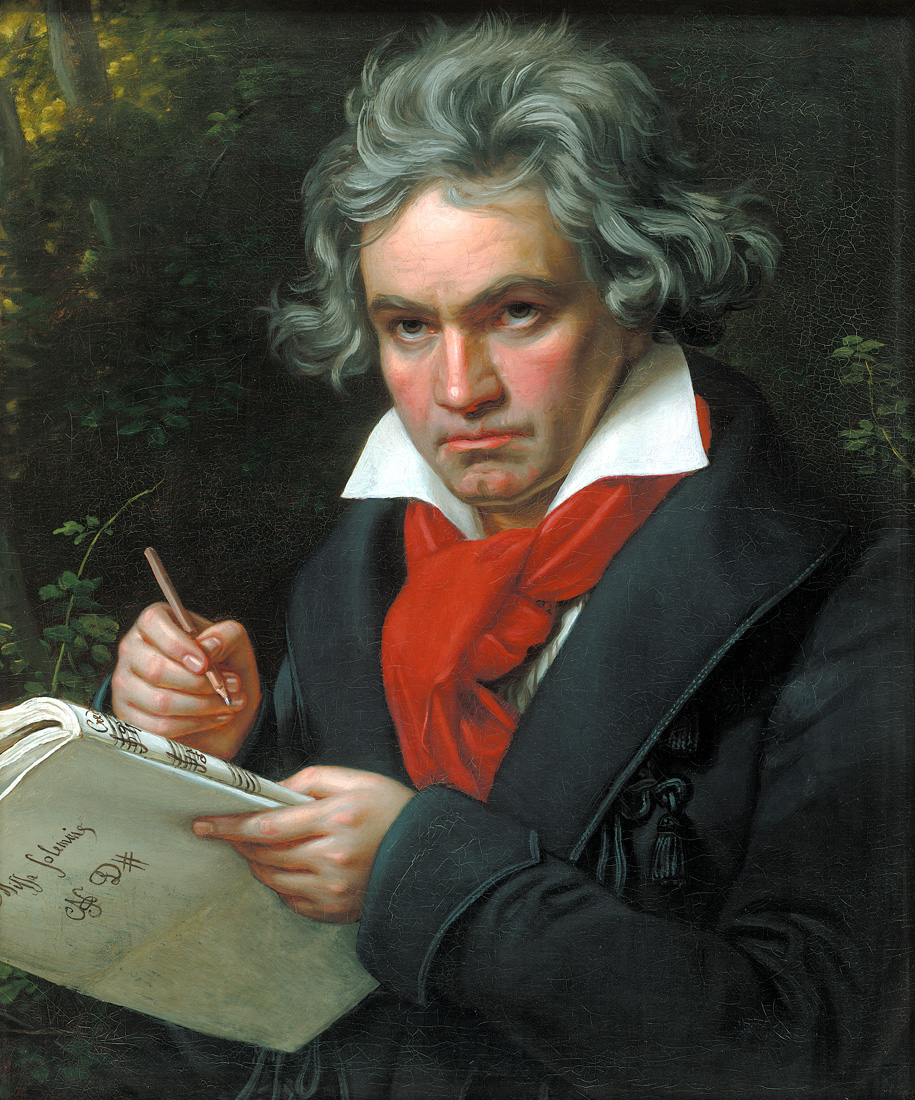

The Composer

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in 1770 in Bonn, grandson of Ludwig van Beethoven who was Kapellmeister at the court of the Elector of Bonn. His father Johann, a tenor, heavy drinker, pushed the young Ludwig in music, hoping he could gain fame as a prodigy like the young Mozart. He performed publicly at age 9, and studied composing with Christian Neefe. In 1792 he moved to Vienna, where he studied, performed as a pianist, was oriented by Haydn – and evidently influenced by Mozart. His first public performance was in 1795, and he composed for solo piano, the string quartet, symphonies for the orchestra and a variety of other music.

From about 1796, Beethoven began to lose his hearing, and by 1801 was quite deaf…… Can one imagine the despair of this, as he whose life is music can gradually no longer discern the subtlety of sound, and then the sound itself? And only communicate with people with great difficulty? In 1802 a depressed Beethoven considered suicide, but then resolved to live through his art – a document called the Heiligenstadt Testament sets out his arguments to himself. In 1803 Beethoven wrote his 3rd Symphony Opus 55, called the Eroica, because of its epic scale and heroic strength. This piece, as well as embodying his triumph over disability, sets new standards for orchestral writing – what could be done with the instrumental resources, with harmonies….. written by a man who could really only hear it in his mind! Up to 1812, his “middle period” Beethoven wrote his Symphonies 3 to 8, string quartets 7 to 11, piano sonatas, the opera Fidelio, the violin concerto. He achieved great status and success.

But then came a period when he wrote little. He could no longer perform in public, and was increasingly shut in his own world. In this late period, from 1816 to his death in 1827 his writing became more experimental, full of innovations. He produced the last five piano sonatas, last two for cello and piano, the late string quartets, the Missa Solemnis – and the 9th Symphony, which for the first time added soloists and a chorus in the final movement. Started in 1818, it was completed in 1824.

The Music

One of the advantages of the 9th is that it is always interesting. Beethoven starts off each movement with a clear statement, very different in each of the four movements, and through each movement he comes back to it, either repeating it, or embellishing it, or surrounding it with different effects, or modulating it in a different form. This gives us a structure to get hold of. And the bits in between are interesting as well. Another thing I find is that there is no sadness or lamentation about this music, no defeatism. Strength there is, yes, and confidence in the force of its expression, even in the calm moments.

The 1st movement Allegro ma non troppo, after a quiet start, explodes to a statement of great dignity, like a martial procession – but then backs off.

And goes thus time and again, building tension then quietening down, remembering the opening……. but in the middle, the tone becomes more afflicted, the strings even stronger

– and when he returns to the opening statement, each phrase is played over a thunder from the timpanos, which builds up an overwhelming sense of strength in tragedy

– before the music quietens again. The crescendos and quiet passages continue, but within a structure which is powerful, grandioso. After the sudden finish one is left with a feeling of awe.

The 2nd movement Molto vivace has the orchestra playing very fast and light, and some of the phrases have a quick tum-b’dum from the timpanos (kettle drums) to set them on their way.

There is a quieter interlude before the strings are off again, very light and precise, being chased by the timpanos. There is a section in the middle with a warm passage from the cellos, complemented by the horn and oboe

before we’re off headlong again, repeating the first part

But just as it looks as if we’re going to do it all again, he cuts it off. Fun.

The 3rd movement is serene – Adagio molto e cantabile, with such a calm dignified melody – like a vast landscape of mountains and forests…

The cellos bring in a lovely second theme, which is later elaborated by the violins and woodwinds

Throughout the movement, Beethoven uses long sustained notes from the orchestra as backing to the melody, together with lightly plucked strings – all adding to the sense of peace.

The 4th movement is monumental, a symphony in itself, with so many changes of tempo. It starts dramatically in loud protest, with the cellos stating the vibrant call – Friends!

– then he intersperses little flashbacks to the previous movements, and a hint of the main theme……and finally there is the well-known melody, introduced pianissimo by the cellos

This is reworked with increasing emphasis by various parts of the orchestra, as it will be throughout the movement. But then the dramatic opening is repeated, and the bass soloist stands up and sings “Friends, not these sounds, rather let us strike up pleasanter and more joyful ones!” And then we’re off, choir and orchestra, using the main theme to express the Ode to Joy….. and to exalt brotherhood

Parts for the soloists are interleaved with parts for the choir and orchestra. In the middle, the tenor has a nice dance-like tune to sing “…run, brothers, your course, joyfully, like a hero towards victory”

while the male voices tell everyone to embrace and send a kiss to the whole world. Some of the most dramatic climaxes are to express “Brothers! Beyond the canopy of the stars a loving Father must dwell”. And so, growing in intensity and strength, we come finally to a wild and satisfying ending.

This CD

This music is sufficiently coherent, entertaining and dramatic to be good in practically any rendition. But this live recording from Furtwängler at the Beyreuth Festival in 1951 is very special. The Festival was reopening after the dark years of the Second World War – a return to light. The event was also a personal vindication for Furtwängler, an acknowledged great conductor with a most profound understanding of Beethoven. As says the critic André Tubeuf – “Furtwängler may have given more incandescent and furiously sublime readings of this immense work. But never had the circumstances been so truly solemn. The recording is there. It has captured a mystical moment in the history of the West”.

Great Listening!